From Diary of the American Revolution, Vol II. Compiled by Frank Moore and published in 1859.

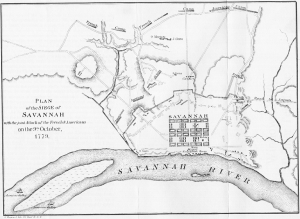

October 22.—On the first day of last month (September) Count D’Estaing arrived off the coast of Georgia, in order to co-operate with the Americans under the command of General Lincoln, in the reduction of Savannah. Upon the fifteenth, says a correspondent, the Count summoned the town to surrender, in the true style of a Frenchman.1 A proper answer was returned. In the mean time Moncrieffe was indefatigable in putting the place in a proper state of defence. A few days afterwards, the French and rebels began to throw up works upon the hill to the left of Tatnall’s, within about three or four hundred yards of the British lines, when three companies of light infantry were sent out in hopes of drawing on a general action; but were obliged to retire, being opposed by ten times their number, after fighting like lions in the sight of the whole army. The British loss was Lieutenant M’Pherson killed, and about fifteen privates killed and wounded; and it is beyond doubt that the French had upwards of fifty killed, and a considerable number wounded. Major Graham commanded in this little affair. After this, the British never attempted to interrupt the Monsieurs, who could be heard working like devils every night.

About one o’clock in the morning of the third instant, they began a most dreadful cannonade and bombardment, which continued with very little intermission until the ninth, when the town was very much shattered, and two houses burnt by carcases. Notwithstanding there were thirty pieces of heavy cannon and ten mortars incessantly playing upon us, it is astonishing the little loss we sustained; the only officer killed was our worthy friend Captain Simpson, of Major Wright’s corps. About daybreak on the ninth, the united forces of France and America, consisting of upwards of four thousand French, and the Lord knows how many rebels, attempted to storm our lines. The principal attack was made in three columns, who intended to unite and attack the works at the redoubt upon the Ebenezer road. The count, in person, began the attack with great vigor, but was soon thrown into confusion by the well-pointed fire from our batteries and redoubts. A choice body of grenadiers came on with such spirit to attack the old redoubt upon the Ebenezer road, that if Tawse, with a number of his men, had not thrown himself in very opportunely, it must have been carried; upwards of sixty men were lying dead in the ditch after the action. Poor Tawse fell bravely fighting for his country. The rebels could not be brought to the charge, and in their confusion are said to have fired upon their allies, and killed upwards of fifty of them. It is almost incredible the trifling loss we sustained; the only officer killed was poor Tawse, and there were not twenty privates killed and wounded. The enemy’s loss was astonishing. I never saw such a dreadful scene, as several hundreds lay dead in a space of a few yards, and the cries of many hundreds wounded was still more distressing to a feeling mind. The exact loss of the enemy cannot be ascertained; but Mr. Robert Baillie, who was a prisoner with the French during the whole of the siege, says they own a loss of near fifteen hundred. The count, in the action of the ninth, was wounded in the arm and thigh, and Pulaski very dangerously by a grape-shot in the groin. Two days ago the last of the French troops embarked; the rebels have been gone some time, and we are now in as much tranquillity as we have been for any time these six months past. Mutual animosity and reviling have arisen to such a height between the French and rebels since they were defeated, that they were almost ready to cut one another’s throats.1

1 The Count summoned General Prevost to surrender to the arms of the King of France. General Lincoln remonstrated with him on his summons to surrender to the arms of France only, while the Americans were acting in conjunction with him. The matter, however, was soon settled, and the mode of all future negotiations amicably adjusted.—Gordon, iii. 81.