An Army Truly Continental:

Expanding Participation

While the Continental Army in the north took shape in 1776, the colonies to the south also turned to military preparations. The process began, much as it had in New England, with the formation of forces by revolutionary governments to oppose British threats in the immediate vicinity of each colony. Congress brought these forces into the Continental establishment and raised others not in accord with a general plan but in response to circumstances, although it did attempt to introduce some order by establishing separate Middle and Southern Departments for administration and command and for expansion of the staff. By the time of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Continental regiments represented every state. When the British then mounted a massive invasion against New York, Washington moved most of his Main Army from Boston and augmented it, under congressional direction, with new Continental units and short-term militia. As units from the south arrived to meet this crisis, the Continental Army began to take on the character of a genuine national force.

The aggressiveness of Governor John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore, led Virginia to act first. When it organized an extra-legal assembly in March 1775, the more radical element led by Patrick Henry was unable to persuade the colony to raise regular troops. The news of Lexington and Concord, however, had produced a change in attitude when the Virginia Convention reconvened in July. Although there was general agreement on the need to take military action, debates over actual measures lasted until 21 August. Proposals for an armed force of 4,000 men were scaled down to three 1,000-man regiments, but they still could not gain approval. The final com-

After reporting to Williamsburg, the fifteen regular companies (about 1,020 men) were organized on 21 October into two regiments. The 1st Virginia Regiment under Patrick Henry contained 2 rifle companies and 6 musket companies; the 2d Virginia Regiment under William Woodford also had 2 rifle companies but only 5 musket companies. The rifle companies—intended as light infantry—came from the frontier districts; the musketmen, from more settled regions. Each had a captain, 2 lieutenants, an ensign, 3 sergeants, a drummer, a fifer, and 68 rank and file. The district committees selected the company officers, while the convention appointed three field officers for each regiment. Regimental staffs contained a chaplain, an adjutant, a paymaster who doubled as mustermaster, a quartermaster, a surgeon with two mates, and a sergeant major. Because Henry was the senior officer, the 1st also had a secretary. The officers of Virginia’s two regiments carried impressive credentials: all were political leaders, and four had significant combat experience. The captains were prominent in local affairs, although most were too young to have served in the French and Indian War.

The compromise which created the two regiments also included five independent companies to garrison strategic frontier posts. They were under the overall command of Capt. John Neville, who established his headquarters at Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh). Four were rather large: a captain, 3 lieutenants, an ensign, 4 sergeants, 2 drummers, 2 fifers, and 100 rank and file; the fifth had only a single lieutenant and 25 enlisted men. Two of the large companies manned Fort Pitt while the small one garrisoned Fort Fincastle at the mouth of the Wheeling River. These three companies were recruited in the West Augusta District, a partially organized region on the northwest frontier. Another company, from Botetourt County, defended Point Pleasant, and the last defended its home county of Fincastle. The use of independent companies followed the British Army’s practice of sending separate units to remote colonial garrisons.2

Skirmishes with Lord Dunmore’s forces in the Hampton Roads area during the late fall culminated in a minor battle at Great Bridge. The Virginia Convention reacted by passing legislation on 11 January to raise 72 more companies of regulars. It

1. William J. Van Screevan et al., eds., Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973- ), 3:319-43, 392-409, 427-29, 450-59, 471-72; 497-504. William Waller Henning, comp., The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, 14 vols. (1821; reprint ed., Charlottesville: Jamestown Foundation, 1969), 9:9-50; George Mason, The Papers of George Mason, 1725-1792, ed. Robert A. Rutland, 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970), 1:245-57; The Virginia Gazette (ed. Alexander Purdie), 25 Aug 75; Brent Tarter, ed., “The Orderly Book of the Second Virginia Regiment, September 27, 1775-April 15, 1776,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 85 (1977):170-71.

2. Van Screevan, Revolutionary Virginia, 3:343, 404; Reuben Gold Thwaites and Louis Phelps Kellogg, eds., The Revolution on the Upper Ohio, 1775-1777 (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1908), pp. 12-17.

The nine regiments, like the frontier companies, were raised as state troops for the defense of Virginia and its neighbors. That fact, the ten-company organization, and the short enlistments made the regiments similar to the earlier Provincials. The financial burden of such a large force, however, soon led the colony to ask that the regiments be transferred to the Continental Army. On 28 December 1775, Congress, which was already moving to broaden the geographical base of the Continental Army, authorized six Virginia regiments. The Virginia delegates engaged in prolonged negotiations before Congress accepted all nine regiments. The 1st and 2d retained seniority by being adopted retroactively; the others came under Continental pay when they were certified as full. Virginia did not alter its regimental organization to conform to Continental standards, and the transfer did not alter the terms of enlistment. It did require the officers to exchange their colony commissions for Continental ones, and a few refused and resigned. When Virginia requested Congress to appoint general officers to command these troops, Washington objected to Henry’s lack of military background and successfully blocked his appointment. In the end, two men who had served under Washington were appointed brigadier generals: Andrew Lewis on 1 March 1776 and Hugh Mercer on 5 June.4

The Virginia Convention had authorized an artillery company on 1 December 1775 consisting of a captain, 3 lieutenants, a sergeant, 4 bombardiers, 8 gunners, and 48 matrosses. On 13 February the Committee of Safety selected James Innis as captain and Charles Harrison, Edward Carrington, and Samuel Denney as lieutenants. Congress adopted the company on 19 March, and soon after instructed Dohicky Arundel, a French volunteer, to raise another artillery company in Virginia. When Innis transferred to the infantry, Arundel attempted to merge the two companies, but

3. Henning, Statutes at Large, 9:75-92; Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 4:78-83, 118; Van Screevan, Revolutionary Virginia, 4:467-69, 497-99; William P. Palmer, ed., Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts, 11 vols. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1875-93), 8:75-149. The 9th expanded to ten companies on 18 May: Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 6:1528, 1556; Henning, Statutes at Large, 9:135-38.

4. JCC, 3:463; 4:132, 181, 235; 5:420, 466, 649; Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 4:116-17; 5th ser., 1:719-22; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 4:379-84; Jefferson, Papers, 1:482-84; Van Screevan, Revolutionary Virginia, 4:421-22, 470-71; Smith, Letters of Delegates, 3:100-102, 123-24, 240, 245-46, 248-49, 252, 316n, 440; Burnett, Letters, 2:31-32.

In May 1776 the colony reorganized the frontier defense companies, for the most part retaining their large size. Reenlistments at Fort Pitt and Point Pleasant filled one company from each place. A third was organized in Botetourt County for duty at Point Pleasant. New, smaller companies (3 officers, 3 sergeants, a drummer, a fifer, and 50 rank and file) were raised in Hampshire and Augusta Counties to garrison Wheeling (Fort Fincastle) and a post on the Little Kanawha River. All were under Neville, who was promoted to major. The same legislation ordered reenlistment of the men of the 1st and 2d Virginia Regiments for three years.6 Virginia’s regular forces were more than a match for Lord Dunmore, and the British soon withdrew to New York.

North Carolina’s revolutionary leadership was less sure than Virginia’s of its popular support and consequently turned to outside assistance sooner. The colony contained many recent Scottish immigrants who were still loyal to the Crown, and old grievances left the backcountry’s willingness to follow Tidewater planters in doubt. On 26 June 1775 the North Carolina delegates secured a congressional promise to fund a force of 1,000 men. This support enabled the colony’s leaders to act.7

Aside from raising the Continental force, North Carolina organized six regional military districts and instructed each to raise a ten-company battalion of minutemen. At the same time, the colony disbanded its volunteer companies to remove any obstacles to recruiting. The minutemen had the same organization as the colony’s Continental companies: 3 officers, 3 sergeants, and 50 rank and file. This structure was quite similar to that of the Virginia minutemen. On 1 September the colony’s 1,000 continentals were arranged in 2 regiments, each consisting of 3 field officers, an adjutant, and 10 companies. The companies assembled at Salisbury beginning in October. The colony’s total response was a compromise. Eastern interests received the two regular regiments to defend the coastline from naval vessels supporting former Governor Josiah Martin. Less threatened areas relied on the less expensive minutemen.8

On 28 November 1775 the Continental Congress ordered both North Carolina regiments reorganized on the new Continental eight-company structure. It went on to authorize a third regiment on 16 January 1776 and two more on 26 March. Colonial concurrence was required to raise the new regiments. However, the Provincial Congress was receptive and on 9 April approved raising the three new regiments for two and a half years. The Continental Congress had already rewarded North Carolina’s prompt actions in 1775 by promoting Cols. James Moore and Robert Howe to brigadier general on 1 March 1776. The Provincial Congress had second thoughts, however, and on 13 April it ordered that its regular forces be reorganized as six instead of five regiments. Five new companies were raised by each of the six military districts, and

5. Henning, Statutes at Large, 9:75-92; JCC, 4:212, 364. Virginia Gazette (Purdie), 16 Feb and 12 Jul 76; Charles Campbell, ed., The Orderly Book of That Portion of the American Army Stationed at or Near Williamsburg, Va., Under the Command of General Andrew Lewis From March 18th, 1776, to August 28th, 1776. (Richmond: privately printed, 1860), pp. 26-27, 36-37; Lee, Papers, 1:367-68, 416-17, 440-43, 477-80; Smith, Letters of Delegates, 3:102n, 108-9, 168-69, 397, 469-70, 570-72.

6. Henning, Statutes at Large, 9:135-38; Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 6:1532, 1556, 1568; Henry Read McIlwaine et al., eds., Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia, 4 vols. (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1931-67), 1:97, 108, 148, 173.

7. JCC, 2:107; 3:330; Smith, Letters of Delegates, 1:545.

8. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 2:255-70; 3:181-210, 679, 1087-94.

Meanwhile, continued concern for the security of the coast had led to a proposal to add another regular regiment, with six companies. General Moore persuaded the Provincial Congress to modify this plan on 29 April. Instead of a seventh regiment, five independent companies of state troops were authorized to defend specific points. Two were standard-sized companies, but the other three each had only sixty privates. On 3 May a 24-man company was added to garrison a frontier fort.10

South Carolina’s situation in 1775 was somewhat similar to North Carolina’s. Again there was lingering tension between the Tidewater and backcountry, but the colony’s leaders were more secure. Like Virginia, the colony decided to supplement the militia with regular state troops rather than turn immediately to the Continental Congress. The Provincial Congress adopted a regional compromise on 4 June. Two 750-man regiments of infantry were authorized to defend the Tidewater from possible attack by regular British troops. The “upcountry” received a third regiment of 450 mounted rangers to counter potential Indian raids. Since there was no immediate danger, the Provincial Congress limited expenses by restricting the companies to cadre strength when it issued recruiting orders on 21 June. The infantry regiments were authorized ten 50-men companies each, a structure similar to that selected by North Carolina and Virginia in 1775. The nine ranger companies were allowed thirty men each. Competition for commissions was intense, and a minor mutiny occurred in some companies of the ranger regiment when the spirit of the regional compromise was violated by the assignment of a Tidewater militia officer as the regimental commander.11

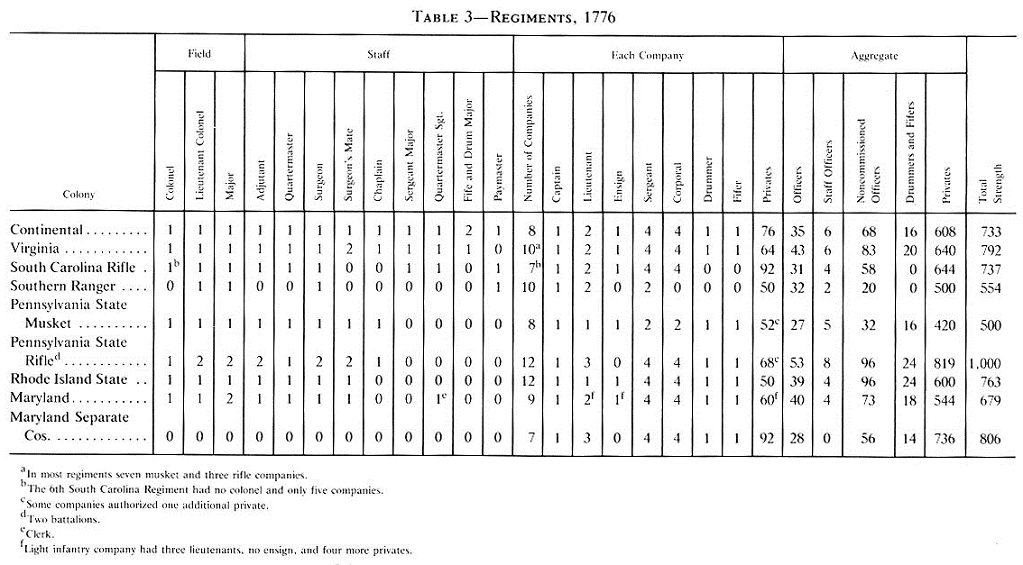

During the winter the South Carolina Provincial Congress expanded its forces. An artillery regiment, small but highly specialized, was established to man the fortifications at Charleston. (Chart 5) The 4th South Carolina Regiment drew its cadre from Charleston’s elite militia artillerymen. A separate artillery contrary authorized at this time to defend Fort Lyttleton at Port Royal was not raised. On 22 February 1776 the three original regiments were finally allowed to recruit to full strength, and shortly thereafter two rifle regiments were added. (See Table 3.) The 5th South Carolina Regiment had seven companies, recruited in the Tidewater. The 6th had only five companies; Thomas Sumter raised this regiment along the northwestern frontier where many of the inhabitants were former Virginians. Each rifle company contained four

9. JCC, 3:387-88; 4:59, 181, 237, 331-33; 5:623-24; 8:567; Smith, Letters of Delegates, 3:18-19, 42-44, 100-103, 123-24, 315-18, 448; Burnett, Letters, 1:448; Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 4:299-308; 5:68, 859-60. 1315-68; 6:1443-58.

10. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 5:1330-31, 1341-42, 1348.

11. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 2:897, 953-54; William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution. So Far As It Related to the States of North and South Carolina and Georgia, 2 vols. (New York: David Longworth, 1802), 1:64-65; John Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution. From Its Commencement to the Year 1776, Inclusive, 2 vols. (Charleston: A. E. Miller, 1821), 1:249, 255, 265, 286-88, 323, 352-53; R. W. Gibbes, ed., Documentary History of the American Revolution, 3 vols. (Columbia and New York: Banner Steam-Power Press and D. Appleton & Co., 1853-57), vol. A, pp. 104-5.