partment during 1776, and in November a congressional delegation directed him to reorganize that department’s artillery forces for the coming year. Using veteran troops at Ticonderoga as cadres, Stevens reorganized three companies using Massachusetts recruits. He recruited a fourth company, composed of artificers to perform maintenance, at Albany from miscellaneous personnel. Stevens believed throughout 1777 that he commanded a separate corps, but in fact his companies were part of Crane’s regiment, which they joined in 1778.24 Two regiments in the Southern Department provided the total of five which Knox had contemplated. One was the 4th South Carolina Regiment. Congress had authorized the other on 26 November 1776 by expanding two existing companies in Virginia into a ten-company regiment under Col. Charles Harrison and Lt. Col. Edward Carrington. It remained in garrison in its home state throughout 1777.25

Knox’s original proposal also encompassed the special logistical requirements of the artillery. He wanted Congress to create a company of artificers, to regroup the staff of the Commissary of Military Stores, and to establish laboratories and a foundry so that the Army could begin producing its own cannon, ammunition, and related items. He and Washington recommended that Congress import weapons from Europe until those facilities came into service. The most essential materiel, they argued, was a mobile train of brass field pieces consistent in makeup with European practice: one hundred 3-pounders, fifty 6-pounders, and fifty 12-pounders, plus a number of heavier 18- and 24-pounders for general support and sieges. Congress promised to obtain these pieces.26

24. Lamb Papers (Oswald to Lamb, 16 Feb 77; Knox to Lamb, 20 Apr and 24 May 77); Fitzpatrick, Writings, 8:276.

25. JCC, 6:981, 995; 8:396, 514, 655; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 8:117; 9:332; 10:520; Virginia Gazette (Dixon and Hunter), 28 Feb 77. The Virginia regiment’s companies contained 4 officers, 1 sergeant, 4 corporals, 4 bombardiers, 8: gunners, and 48 matrosses.

26. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 6:280-82; JCC, 6:963.

During the winter Washington and Knox addressed the problem of improving the mobility of the field artillery to furnish direct support to the infantry. During the Trenton campaign each infantry brigade had been supported by a company of artillery with two to four guns. This experiment proved so successful that the concept of a direct support company remained a fixture of the Continental Army for the remainder of the war. Other artillery companies served in the artillery park or manned the heavy garrison artillery of fixed fortifications. The brigade support company, preferably from the same state as the infantry, varied its armament according to the brigade’s particular mission. The ideal armament consisted of two 6-pounders in 1777, although this weapon required the largest crew of any field piece—twelve to fifteen men including an officer. Since doctrine called for concentrated fire on enemy infantry, rate of fire and maneuverability were more important than range.28

During 1775 and 1776 the Continental Army relied primarily on old British artillery pieces imported during the colonial period or captured in the first actions of the war. The other source of cannon was domestic production of iron guns. The American iron industry was producing 30,000 tons of bar and pig iron in 1775, one-seventh of the world’s total. It quickly turned to military production. Unfortunately, these sources contributed few weapons suitable for battlefield use. Most cannon were so heavy that they were limited to permanent fortifications. Washington counted on the foundry in Philadelphia and foreign imports to provide the lighter brass guns for the direct support companies.29

The imports came primarily from France. The French and, to a lesser extent, the Spanish governments furnished clandestine aid to the American colonies through the firm of Hortalez and Company in the hope of weakening Great Britain. Indirectly at

27. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 6:474; 7:18-23; 8:38; Pennsylvania Archives, 1st ser., 5:209-10.

28. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 6:364, 454; 8:100-101, 175, 235, 318-21, 396-99, 457-58; 9:290; Lamb Papers (Oswald to Lamb, 17 and 25 Jun. 23 and 25 Jul. and 14 Aug 77; Walker to Lamb, 21 Jul 77; Moodie to Lamb, 9 May 77; Knox to Lamb, 2 Dec 77). Washington similarly sought to improve the maneuverability of ammunition wagons: Fitzpatrick, Writings, 7:83.

29. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 4:534-35; Fairfax Downey, “Birth of the Continental Artillery,” Military Collector and Historian 7 (1955):61-62; Keach Johnson, “The Genesis of the Baltimore Ironworks,” Journal of Southern History 19 (1953):151-79; Irene D. Neu, “The Iron Plantations of Colonial New York,” New York History 33 (1952):3-24; Spencer C. Tucker, “Cannon Founders of the American Revolution,” National Defense 60 (1975):33-37; Salay, “Arming for War,” pp. 202, 241-75; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 7:69; 8:37.

The Continental Army’s artillerymen turned to John Muller’s Treatise of Artillery as a handbook for mounting these guns and casting their own. Muller’s work had first appeared in 1757 as a textbook for the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, and an American edition appeared in Philadelphia in 1779 dedicated to the Continental Artillery. His proposals were particularly important to Americans for he called for mobile iron guns and offered detailed instructions for casting them and for constructing light carriages.31

The emphasis on mobility extended to the third element in Congress’ 27 December legislation. Unlike the additional infantry regiments and the expanded artillery, the 3,000 light horse represented a new element in the Continental Army. Most European armies still used heavy cavalry as an offensive battlefield force. During the middle of the century a renewed interest in reconnaissance and skirmishing had led to the return of some light horsemen. The terrain in America had eliminated the need for heavy cavalry during the colonial period, although some troopers had served as messengers or scouts. By the start of the Revolution a few colonies had regiments of mounted men, but they were mobile infantry rather than true cavalry. The cost of owning, feeding, and equipping a horse ensured that the men of such units came from the social elite.

The British Army’s large cavalry contingent was organized for European combat. As a result, only two light cavalry regiments served in America during the Revolution. The 17th Light Dragoons arrived in Boston in May 1775 and served throughout the war; the 16th reached New York in October 1776 and remained for only two years. Each regiment consisted of six troops plus a small headquarters consisting of a titular colonel, a lieutenant colonel, a major, an adjutant, a chaplain, and a surgeon. Each troop initially contained a captain, a lieutenant, a cornet (equivalent to an infantry ensign), a quartermaster, 2 sergeants, 2 corporals, a hautboy (drummer), and 38 privates. In the spring of 1776 the establishment of a troop was increased by another cornet, a sergeant, 2 corporals, and 30 privates. General Howe was given the option of either mounting the augmentation with locally procured horses or using the men as light infantry.32 One German cavalry regiment, the Brunswick Dragoon Regiment von Riedesel, served in Canada, but as infantry.33

Several times during 1775 and 1776 Congress toyed with the idea of adding mounted units to the Continental forces in the north, but it did not act since operations were largely static. The ranger regiments authorized in 1776 in the south were

30. Force, American Archives, 5th ser., 1:1011-23; Burnett, Letters, 2:218-19, 591; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 8:2-3, 37, 254, 318-19.

31. John Muller, A Treatise of Artillery, ad ed. (London: John Millan, 1780; reprint, with introduction by Harold L. Peterson, Ottawa: Museum Restoration Service, 1965), pp. v-xxv; Sebastian Bauman Papers (to Lamb, 25 Jun 79; Samuel Shaw to Bauman, 17 Feb 77), New-York Historical Society.

32. British Headquarters Papers, No. 27 (Barrington to Gage, 31 Aug 75), 114, 491 (Barrington to Howe, 29 Jan 76 and 16 Apr 77).

33. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 6:271-73. It had 4 troops, each with 3 officers and 75 men, plus a staff of 8 officers and 16 men.

Congress’ initial response came on 25 November 1776 when it requested Virginia to transfer Maj. Theodorick Bland’s six troops of light horse to the Continental Army. The state had raised them during the summer. Each contained 3 officers, 3 corporals, a drummer, a trumpeter, and 29 privates. Three quartermasters provided logistical support for the group. Virginia complied, and in March 1777 Bland reenlisted his troops as continentals and reorganized them into a regiment.35 On 12 December Congress, at Washington’s suggestion, directed Sheldon to raise a Continental regiment of light dragoons and appointed him lieutenant colonel commandant of cavalry, a rank equivalent to colonel of infantry. Washington gave Sheldon the same free hand in selecting junior officers that he delegated to the colonels of the additional regiments.36

Congress’ 27 December resolve then allowed Washington to raise up to 3,000 light dragoons, and to determine how they should be organized. Washington interpreted the legislation to mean that Bland’s and Sheldon’s men were included in the authorized figure, and he decided to add only two more regiments. He wanted to see if he could fill them before he tried to raise others. At the request of Congress, command of one of the new units went to Washington’s aide George Baylor, who had carried the news of the Trenton victory to Baltimore. Lt. George Lewis of the Commander in Chief’s Guard became one of his captains. The other regiment went to Stephen Moylan, another aide, who had served as Mustermaster General and Quartermaster General.37

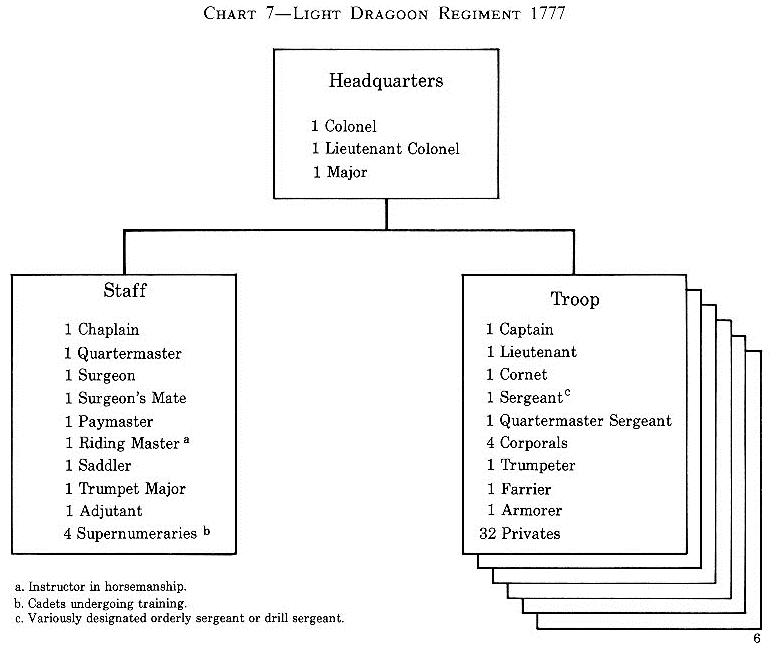

On 14 March 1777 Congress approved Washington’s regimental organization for the light dragoons. (Chart 7) It provided 3 field officers, a staff, and 6 troops for each regiment. Every troop contained 3 officers, 6 noncommissioned officers, a trumpeter, and 34 privates. One of the sergeants specialized in logistics, and two privates, an armorer and a farrier, received higher pay. The farrier provided rudimentary veterinary care and shod the horses. The staff was similar to an infantry regiment’s, with the addition of a riding instructor and a saddler to keep leather gear in repair. Four supernumeraries were cadets undergoing training who served the colonel as messengers. The Continental light dragoon regiment was comparable to the British version, but it provided more specialists on both the troop and regimental level to allow greater dispersion on reconnaissance missions.38

Washington believed that the light dragoons’ primary mission was reconnaissance, not combat. He instructed his troopers to use inconspicuous dark horses and ordered

34. JCC, 2:173, 238; 5:606-7; Smith, Letters of Delegates, 1:587, 590-91; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 5:163-64, 236-37, 242, 324; 6:39, 230-31.

35. JCC, 6:980; 7:34; Burnett, Letters, 2:269; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 6:456-57; 7:103, 338-39; Henning, Statutes at Large; 9:135-38, 141-43; McIlwaine et al., Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia, 1:153, 254-55, 269, 288; Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 6:1531, 1556; 5th ser., 3:1270.

36. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 6:350-51, 384, 386-88; JCC, 6:1025; Burnett, Letters, 2:176.

37. JCC, 7:7; Fitzpatrick, Writings, 6:483-84; 7:51, 193-94, 304-5.

38. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 12:290; JCC, 7:178-79; 9:869; Sullivan, Letters and Papers, 1:403. Sheldon’s regiment operated with a slightly different configuration until 5 November 1777.

39. Fitzpatrick, Writings, 7:123, 214-15, 219-20, 324, 368, 421; 8:53-54, 136, 264-65.

The states of the lower south had the easiest time adjusting to the new quotas because their regiments remained in their home states as the Southern Department’s primary combat forces. Georgia did not reduce its force to the single regiment of the 16 September quota but retained the four infantry and one ranger units authorized during 1776. The rangers and the 1st Georgia Regiment lost strength during the spring as original enlistments expired, but the 2d and 3d reached operational strength through extensive recruiting in North Carolina and Virginia. The 4th Georgia Regiment kept enlisting men from as far away as Pennsylvania into October 1777.40 The six South Carolina regiments adjusted to the new organizational structures by additional recruiting. The two rifle regiments (the 5th and 6th South Carolina Regiments) converted to infantry, and half of the 3d exchanged rifles for muskets. The 4th remained an artillery regiment, absorbing the separate artillery companies. Recruiting remained a major problem, and officers ranged as far as Pennsylvania in a search for volunteers.41

The regiments from North Carolina and Virginia did not remain at the disposal of the Southern Department commander, Brig. Gen. Robert Howe, but joined the Main Army. The 8th Virginia Regiment and various North Carolina detachments stationed in South Carolina returned to their home states during the spring to be refilled.42 Since the current enlistment period of the six North Carolina and nine Virginia regiments lasted until 1778, they remained unchanged. North Carolina’s government raised three more regiments during the spring to meet its quota, although it felt that the total was unreasonably high. All nine North Carolina regiments reached Philadelphia in early July, but only two of the regiments mustered over 200 effectives, and the nine totaled only 131 officers and 963 enlisted men. They should have contained an aggregate of about 7,000.43

Five Virginia regiments joined Washington in late 1776, and 10 others followed in the spring. In addition to the 9 existing units, the state raised 6 new ones following the same techniques it had employed in 1775 and 1776. Virginia was the only state that rejected the standard infantry structure and formed ten companies for each regiment. It also enlisted its men for only three-year terms, not for the duration as Congress preferred. Four of the new regiments were organized from scratch, but two contained cadres already in existence. Col. Daniel Morgan, recently released from captivity, built his 11th Virginia Regiment around the five Virginia companies from the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment and the survivors of his original 1775 rifle company. Col. James Wood’s 12th Virginia Regiment contained the five state frontier companies, who had reenlisted as Continental units. Maj. John Neville, their former commander, became Wood’s lieutenant colonel. The state raised two infantry and one

40. McIntosh, “Papers,” 38:256-57, 266-67, 357-59, 363-67; Margaret Godley, ed., “Minutes of the Executive Council, May 7 Through October 14, 1777,” Georgia Historical Quarterly 34 (1950):110-13; JCC 9:782-83.

41. Force, American Archives, 5th ser., 3:49-54, 66, 68, 72-76; Burnett, Letters, 2:452; Pinckney, “Letters,” 58:77-79.

42. JCC, 5:733-34; 6:1043-44; 7:21, 52, 90-91, 133.

43. Force, American Archives, 5th ser., 1:1384; Burnett, Letters, 2:95-97; Gates Papers (Returns of Troops at Philadelphia, 7 and 8 Jul 77).